La publication de De profondeur de nos cœurs, où Benoît XVI apparaît comme auteur second, est de facto un acte à portée institutionnelle, ce qu’ont immédiatement compris tous les commentateurs progressistes catholiques ou extérieurs. La requête du cardinal Sarah (« Je supplie humblement le Pape François de nous protéger définitivement d’une telle éventualité en mettant son veto à tout affaiblissement de la loi du célibat sacerdotal, même limité à l’une ou l’autre région »), y devient d’abord une demande de Benoît XVI.

Or, Benoît XVI avait solennellement déclaré, lors de sa renonciation en 2013, qu’il « n’interviendrait pas » sur le pontificat de son successeur. Et cependant, il s’était retiré au sein même de l’État du Vatican, conservant la soutane blanche des papes et s’accordant le titre de « pape émérite » qu’on traite de « Sainteté », ce qui pouvait rendre le silence difficile à tenir.

On l’avait bien vu lorsqu’il avait publié une préface pour l’édition en russe de son ouvrage La théologie de la liturgie, en 2017, où il s’élevait contre l’oubli de la priorité de Dieu dans la liturgie, et surtout quand il avait fait paraître, en avril 2019, une longue analyse sur la crise de la pédophilie. Par ailleurs, on savait qu’il ne se faisait pas faute d’exprimer, auprès de ses visiteurs, ses inquiétudes, notamment lors de la transformation brutale de l’Institut Jean-Paul II sur le mariage et la famille.

Qui plus est, le 20 mai 2016, Mgr Gänswein, Préfet de la Maison Pontificale et secrétaire du pape émérite, dans une conférence à l’Université Grégorienne, avait traité de l’« élargissement du ministère pétrinien » : depuis l’élection du 13 mars 2013, disait-il, « il n’y a pas deux papes, mais un ministère élargi, avec un membre actif et un membre contemplatif ». Deux formes, ordinaire et extraordinaire, d’un unique pape, si l’on veut…

De sorte que l’intervention de Benoît XVI aux côtés du cardinal Sarah prend un poids tout particulier. En y mettant toutes les formes possibles du respect, il pose des bornes à l’enseignement pontifical de son successeur. Ce qui ne peutqu’apparaître, dans la perspective de l’avenir à moyen terme, c’est-à-dire dans celui du futur conclave, que comme une tentative de contrecarrer une ligne de transformation libérale de l’Église.

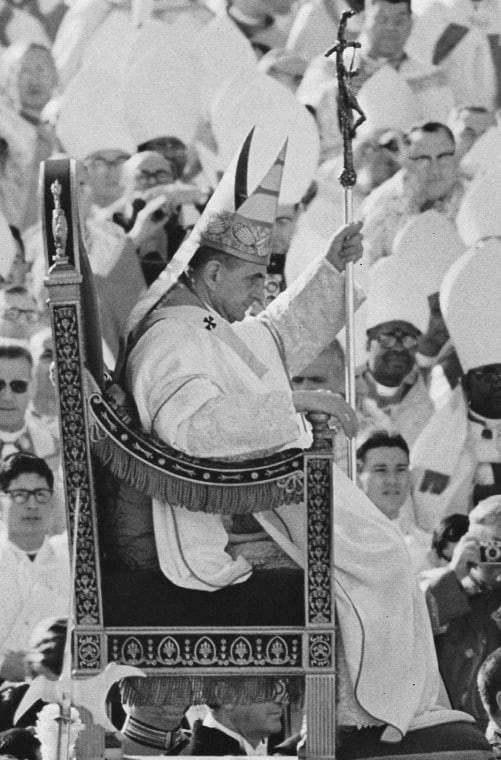

On pourrait certes relativiser la portée de la prise de position du pape émérite, en remarquant qu’elle intervient dans le contexte du débat circonscrit par le post-Concile : depuis un demi-siècle, s’opposent deux interprétations de Vatican II, qualifiées par le même Benoît XVI, dans son discours à la Curie romaine du 22 décembre 2005, d’« herméneutique du renouveau dans la continuité », qui entend le modérer, et « l’herméneutique de la discontinuité et de la rupture », qui entend au contraire l’activer au maximum. D’ailleurs, les documents pontificaux invoqués par Des profondeurs de nos cœurs en faveur du célibat sacerdotal sont ceux de Paul VI, Jean-Paul II, Benoît XVI. Mais on pourrait invoquer l’encyclique de Pie XI, Ad Catholici Sacerdotii, du 20 décembre 1935, l’encyclique de Pie XII, Sacra Virginitas, du 25 mars 1954, et de nombreux papes et concile. Car il faut plus que jamais tenir que l’Église n’a pas commencé en 1965.

D’autant que la période conciliaire a été celle d’une énorme commotion pour le catholicisme. Dans son intervention d’avril 2019 à propos de la crise de la pédophilie, Benoît XVI incriminait le bouleversement social considérable qu’avait représenté Mai 68 avec sa « liberté sexuelle totale, liberté qui ne tolérait plus aucune norme ». Ne serait-il pas opportun d’examiner – au sens d’examen de conscience – le chambardement dans le dogme et la morale qui a été la suite concrète de Vatican II pris comme événement global, dès son achèvement en décembre1965 ? Car la remise en cause théorique et pratique – ces « départs » du sacerdoce, qui ont constitué et constituent toujours une catastrophique hémorragie – du célibat des prêtres a historiquement commencé à la fin de ce concile. C’est indiscutable. Comme le remarque Guillaume Cuchet dans son livre Comment notre monde a cessé d’être chrétien (Seuil, 2018), les textes de Vatican II ont été entendus, selon lui à tort, comme une invitation à la liberté des catholiques par rapport à leur institution.

De sorte qu’on ne pourra éviter à terme de reconsidérer radicalement un aggiornamento qui s’est concrètement présenté comme une nouvelle et très achevée version du catholicisme libéral, cherchant à adapter le catholicisme à cette société moderne, dont la caractéristique fondatrice est la marginalisation, puis l’effacement de la religion du Christ. Et de ses prêtres

.

The Church did not start in 1965

The publication of From the Depth of our Hearts, where Benedict XVI appears as co-author, is de facto an act that carries a constitutional weight, which was immediately understood by all the progressive commentators catholic and non-catholic alike. In this book, the request of Cardinal Sarah (“I humbly beg Pope Francis to protect us, once and for all, from such eventuality by putting his veto to all weakening of the law of the priestly celibacy, even limited to one region or an other”), becomes first a request of Benedict XVI.

During his renunciation in 2013, Benedict XVI had solemnly declared that he “would not intervene regarding the pontificate of his successor. And yet, he had retired in the very State of the Vatican, kept the white cassock of the popes and gave himself the title of “pope emeritus” and is addressed as “holiness”. All this could definitely render his silence difficult to keep.

We saw it clearly when he had published a preface for the edition in Russian of his book The theology of the liturgy, in 2017, where he decried the forgetting of the priority of God in the liturgy, and most of all when he had published, in April 2019, a long analysis on the pedophilia crisis. Also, it was known he often mentioned to his visitors his worries, notably during the brutal transformation of the John Paul II Institute on marriage and family.

Furthermore, on 20th May 2016, Mgr Gänswein, Prefect of the Pontifical house and secretary to the pope emeritus, in a conference at the Gregorian University, had talked about the “expanded Petrine ministry”: since the election of 13th May 2013, he says, “ there are not two popes but an expanded ministry, with an active member and a contemplative member”. Two forms, ordinary and extraordinary, of one pope, if you wish…

In this way, the intervention of Benedict XVI next to Cardinal Sarah takes a particular importance. While including all possible forms of respects, he imposes limits to the pontifical teaching of his successor. In the perspective of the not so distant future, that is to say the future conclave, this can only appear as a tentative to counteract a line of liberal transformation of the Church.

We could certainly put into perspective the stance taken by the pope emeritus, by noticing it appears in the context of the debate circumscribed by the post-council: since a half century, two interpretations of Vatican II oppose each other, qualified by the same Benedict XVI, in his speech to the Roman Curia on 22 December 2005, of “hermeneutic of renewal in the continuity” which wants to moderate it, and the “hermeneutic of discontinuity and of rupture” which wants to push it to its maximum. Actually, the pontifical documents mentioned in From the Depth of our Hearts, in favor of the priestly celibacy, are those of Paul VI, John Paul II, and Benedict XVI. But one could invoke the encyclical of Pius XI, Ad Catholici Sacerdotii, of 20th December 1935, the encyclical of Pius XII, Sacra Virginitas, of 25th March 1954, and many other popes and councils. For we must, more than ever, hold firm that the Church did not start in 1965.

Especially, since the conciliar era was one of a very great commotion for Catholicism. In its intervention April 2019 regarding the pedophilia crisis, Benedict XVI incriminated the “social havoc of May 1968 with its complete sexual freedom, a freedom that no longer tolerated any norms.” Wouldn’t it be opportune to examine – in the sense of an examination of conscience – the chaos in dogma and moral which was the tangible consequence of Vatican II taken as a global event, as soon as its completion in December 1965 ? Indeed, the theoretical and practical questioning – these “departures” from the priesthood, which have constituted and still constitute a catastrophic loss – of priestly celibacy historically started at the end of the council. This is indisputable. As Guillaume Cuchet writes it in his book How our world has ceased to be Christian (Seuil, 2018), the texts of Vatican II have been heard, according to the author, wrongly, as an invitation to freedom for Catholics in relation to the institution.

So that, at some point, we will not be able to avoid radically reconsidering an aggiornamento which really presented itself like a new and very completed version of liberal Catholicism, looking to adapt Catholicism to modern society which founding characteristic is the marginalization, then the obliteration of the religion of Christ. And of its priests.

La Chiesa non è nata nel 1965…

La pubblicazione di Dal profondo dei nostri cuori, in cui Benedetto XVI appare come coautore, è in effetti un atto dal significato istituzionale, cosa chiara sin da subito a tutti i progressisti cattolici e ai commentatori esterni. La richiesta del cardinale Sarah (« Supplico Papa Francesco di proteggerci definitivamente da tale eventualità ponendo il veto a qualsiasi indebolimento della legge del celibato sacerdotale, anche se limitato all’una o all’altra regione »), si pone di fatto come una richiesta di Benedetto XVI.

Nel 2013, al momento della sua rinuncia, Benedetto XVI aveva solennemente dichiarato che non sarebbe « intervenuto » nel pontificato del suo successore. Si era poi ritirato all’interno dello stesso Stato Vaticano, conservando la tonaca bianca dei papi e concedendosi il titolo di « papa emerito » con l’appellativo di « Santità ». Una tale scelta, in effetti, poteva rendere difficile il suo proposito di rimanere in silenzio.

Tutto questo è divenuto evidente quando, nel 2017, il Papa emerito ha pubblicato una prefazione per l’edizione russa della sua opera Teologia della liturgia, nella quale si è espresso contro la dimenticanza della priorità di Dio nella liturgia, e poi quando, nell’aprile 2019, ha pubblicato una lunga analisi sulla crisi della pedofilia. D’altra parte, era fatto noto che Benedetto esprimesse abitualmente le proprie preoccupazioni ai suoi visitatori, in particolare durante la brutale trasformazione del Pontificio Istituto Giovanni Paolo II per studi matrimonio e famiglia.

Il 20 maggio 2016, il vescovo Gänswein, prefetto della Casa Pontificia e segretario del Papa emerito, in un convegno presso l’Università Gregoriana, ha parlato di espansione del ministero petrino: “Dall’elezione del suo successore, Papa Francesco – il 13 marzo 2013 – non ci sono due Papi, ma di fatto un ministero allargato con un membro attivo e uno contemplativo”. Se vogliamo, due forme di un unico papa, una ordinaria e l’altra straordinaria…

Così l’intervento di Benedetto XVI al fianco del cardinale Sarah assume un peso particolare. Con tutto il rispetto del caso, egli pone dei limiti all’insegnamento pontificio del suo successore. In una prospettiva del futuro a medio termine, cioè in quello del futuro conclave, questo non può che apparire come un tentativo di ostacolare una linea di trasformazione liberale della Chiesa.

È senz’altro possibile relativizzare il significato della posizione assunta dal Papa emerito, rilevando che essa interviene in un contesto del dibattito circoscritto dal postconcilio. Da mezzo secolo si oppongono infatti due interpretazioni del Vaticano II, descritte dallo stesso Benedetto XVI nel suo discorso alla Curia romana del 22 dicembre 2005 come « ermeneutica del rinnovamento nella continuità », che intende moderarlo, e « ermeneutica della discontinuità e della rottura », che al contrario intende accelerarlo. I documenti pontifici invocati da Dal profondo dei nostri cuori a favore del celibato sacerdotale sono quelli di Paolo VI, Giovanni Paolo II e Benedetto XVI. Ma potremmo invocare l’enciclica Ad Catholici Sacerdotii di Pio XI del 20 dicembre 1935, l’enciclica Sacra Virginitas di Pio XII del 25 marzo 1954, e molti papi e concili. Perché è più che mai necessario (ricordare) che la Chiesa non sia iniziata nel 1965.

Tanto più che il periodo conciliare è stato quello di un enorme tumulto per il cattolicesimo. Nel suo discorso dell’aprile 2019 sulla crisi della pedofilia, Benedetto XVI ha messo sotto accusa il profondo sconvolgimento sociale che il maggio 68 aveva rappresentato con la sua » totale libertà sessuale, una libertà che non concedeva più alcuna norma”. Non sarebbe opportuno esaminare – nel senso di fare un vero e proprio esame di coscienza – lo sconvolgimento del dogma e della morale che fu la conseguenza concreta del Vaticano II, considerato come evento globale, a partire dalla sua conclisione nel dicembre del 1965? Poiché la messa in discussione teorica e pratica – gli abbandoni del sacerdozio sono stati e sono anche oggi una catastrofica emorragia – del celibato sacerdotale è storicamente cominciata alla fine di quel Concilio. Questo è indiscutibile. Come osserva Guillaume Cuchet nel suo libro Comment notre monde a cessé d’être chrétien, Seuil, 2018 (Come il nostro mondo ha smesso di essere cristiano), i testi del Vaticano II sono stati, secondo lui, erroneamente intesi come un invito alla libertà dei cattolici dalla loro istituzione.

A lungo termine, non possiamo quindi evitare di riconsiderare radicalmente l’aggiornamento che si è concretamente presentato come una versione nuova completa del cattolicesimo liberale, che ha cercato di adattare il cattolicesimo alla società moderna, la cui caratteristica fondativa è l’emarginazione e poi l’annientamento della religione di Cristo. E dei i suoi sacerdoti.